How Fossils Confirmed the Dance of the Continents

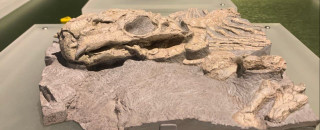

Fossils of Lystrosaurus, like this one in the Antarctic Dinosaurs exhibit, were key to tracking traveling continents. Credit: Riley Black

By Riley Black

The world is always changing. Even now, Earth's continents are moving and shifting at different rates just as they have for hundreds of millions of years. But while this idea is common knowledge now, it wasn't always so. The idea of continental drift was treated as very controversial through most of the 20th century. It took some special fossils to confirm what geologists had suspected.

Naturalists have been pondering the movement of continents since the 16th century, at least. The shapes of Europe and the Americas seemed to hint that they had been torn away from each other or otherwise pulled apart. But how? No one could explain why, and many experts believed that the Earth had always been in its present shape. Still, the idea just wouldn't go away. Geologists Frank Bursley Taylor and Alfred Wegener independently revived the idea at the beginning of the 20th century, Wegener coining the term "continental drift."

Taylor and Wegener's peers were not impressed. Called "fixists" by historians, opposing scientists argued that Earth's continents had been more or less in the same place through time. There was no mechanism to explain how continents might move. Over time, however, geologists turned up evidence that the continents really were in motion. Instead of being anchored deeply to the Earth, continents floated on the Earth's upper layer and could be pushed and pulled around. Great ocean rifts created new ocean rifts to make new seafloor, continental crust could be subsumed in collisions, and some mountain ranges showed signs that they had been pushed up when landmasses met. While molten rock oozes out of the middle of the Atlantic to create new seafloor to push continents on either side apart, places like Africa's eastern rift valley are being pulled in opposite directions by different teconic forces and will eventually split.

The big idea is built on two interrelated concepts. The top layers of the Earth are split into plates. Those plates sit over the Earth's mantle, and the mantle dissipates heat just like a giant convection oven. This provides much of the energy for the processes that move the plates, resulting in continental drift. Plate tectonics is the process, and continental drift is the resulting pattern. If we could fast-forward 10, 100, or 1,000 million years in the future, Earth would look very different than it does now.

Finding how the Earth moves was just part of the story. Fossils had a role to play, too. Paleontologists kept finding similar animals in very distant places, and Wegener cited this evidence in his research. How could experts explain the same species showing up an ocean apart if those continents had never moved? Some appealed to vanished land bridges that once connected continents, but confirmed examples were very few (like the land bridge that connected North America and Eurasia during the last Ice Age). Something else was at play, and fossils from Antarctica offered an answer.

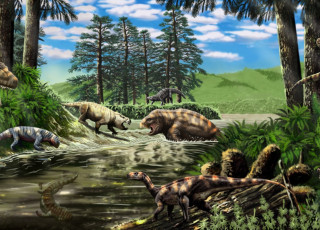

Explorers and paleontologists who braved the harsh conditions of Antarctica found a prehistoric seed fern called Glossopteris that grew about 260 million years ago. This plant had also been found in places like India and Africa in rocks of similar age. Animals upheld the connection, too. In strata dating to the beginning of the Triassic Period, about 250 million years ago, paleontologists found fossils of protomammals like the weasel-like Thrinaxodon and the tubby, tusked Lystrosaurus. These distant relatives of ours had been found rocks of the same age in South Africa. These animals were not adapted to swimming and couldn't have made the swim from prehistoric South Africa to Antarctica even if a pathway existed for them to do so. In 1970 geologist David Elliot and colleagues published a report on these animals and how there could no longer be any doubt that continental drift had shaped the world over eons. Follow the fossils and you can piece together a map of how the world once was.

Riley Black is the author of Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.