From Ashes to Action: Hope Under the Smoke

Note: This article was published in advance of a talk and book signing by the acclaimed author John Vaillant, who was hosted at NHMU by the American West Center. His visit adds to a tradition of NHMU hosting exceptional speakers in Salt Lake City—a tradition that is also celebrated through the annual Lecture Series, which brings thought-provoking voices and stories to our community.

By Olivia Barney

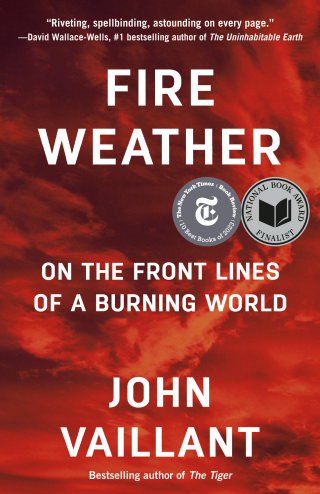

Fire Weather: Weather parameters that influence fire occurrence and subsequent fire behaviour (Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary)

Fire Weather by John Vaillant (cover)

In the aftermath of the costliest disaster in Canadian history, internationally acclaimed author, John Vaillant, put pen to paper — spending the next seven years consumed by his efforts to tell the story of the Fort McMurray wildfire. It was an enormous undertaking. Reporting on the physical and psychological effects of the disaster at Fort McMurray was nearly as surreal as the fire that melted the residents’ cars and turned their homes into firebombs.

In one unseasonably hot afternoon, the hub of Canada’s oil industry was set ablaze, driving 88,000 people from their homes. As John describes it, it was “the wildfire equivalent of Hurricane Katrina.” It didn’t just burn. It caused an entire city to vanish, transforming the lingering concrete foundations at a molecular level. The energy released by the Fort McMurray fire was comparable only to that of multiple nuclear explosions.

How is that possible? Vaillant explains that the chemistry and physics of fire are the same as they’ve always been. The trees are nearly identical to those that stood 100 years ago. It’s the air that is hotter. It’s the soil that is drier. Increasing temperatures and dry landscapes act as catalysts that turn expected wildfires into unthinkable disasters. As the world grows hotter, it is easier for fires to ignite and harder for wildfire crews to extinguish them.

“The world is changing — not ending.”

John Vaillant will be speaking at the Natural History Museum of Utah on Nov. 7, 2024, at a free event. Ahead of his visit, NHMU sat down with him to discuss the reality that current and future generations are facing given the changing climate. We discussed the common narratives surrounding climate change, which often inspire feelings of guilt or overwhelm.

While Vaillant’s latest novel, “Fire Weather,” is an immersive account of a formidable new reality, his tone is decidedly accusation free. It’s a factual view of an issue that often inspires an emotional response. “I wanted it to be a welcoming place,” he explains, “not a punitive place. I want to encourage people to push past the guilt. This is not a purity test — it’s an intellectual exercise. We don’t need to cast moral judgments if we approach it from a chemistry perspective.”

His calm, matter-of-fact demeanor was refreshingly optimistic without being rose-colored. “We don’t know how the story ends,” he reminds. “We’re all facing this, and you have a lot of allies.” Vaillant pointed out that humans, as a species, work best in small groups: families and communities. He encourages individuals to look around their neighborhoods and contribute to the conversations and developments happening there.

1 of 5

"Caring for the climate is a practice. You get up each day and choose to develop yourself and your community.”

Amid a global discussion, it’s easy to feel lost. Unless you have the resources to enact large scale change, the influence to facilitate community-wide conversations, or the education that qualifies you as an expert, it can be difficult to find your place within the climate conversation.

Vaillant’s response to this dilemma is once again encouraging. On such a large-scale project, where there is plenty to do, Vaillant encourages people to do something that excites them — something that uses their unique talents. To those who might feel overwhelmed, Vaillant suggests a realistic approach. “Get real. Get humble. There’s arrogance in thinking you can [do] everything; you can’t. But you can [do] some things.”

Ahead of visiting the University of Utah and surrounding communities, Vaillant extends an additional invitation to the students and young professionals in the area. “Ask yourself what you want to buy. Ask yourself who you want to elect. How you act sends a signal to businesses and leaders, showing them what you want more of.”

A Climate of Hope

Inspired by Vaillant’s invitations? NHMU’s A Climate of Hope exhibition offers a path to rational hope in what is often perceived as a hopeless situation. The exhibition explores the impacts of climate change in Utah before celebrating solutions that have been developed — right here in our home state. With ideas on how to connect with climate action at a local level, this exhibition helps guests identify how their talents can contribute to the community. Prepare for an insightful evening with John Vaillant by checking out A Climate of Hope ahead of time.

This exhibition is included with museum admission, which is free for Museum Members. The Natural History Museum of Utah is open seven days a week, 361 days a year — ensuring year-round exploration and endless family fun.

1 of 3