How To Survive a Mass Extinction: Looking to the Crocs

By Olivia Barney

Extinction, for all species, is eventually inevitable. Over the course of millions of years, every species will face one of two options: extinction or evolution. Evolution involves adapting in some way to better survive amid the challenges of the world they live in. This can include seemingly simple adaptations, like a change in diet or habitat, or something more extreme, like moving from the sky to the sea — the way ancient penguins gave up the ability to fly to become expert fishermen.

Although there are plenty of examples of adaptation and speciation throughout the Earth’s history, the ultimate fate for every species is eventual extinction. This naturally happens over the course of millions of years (and at a relatively steady rate). These two outcomes normally balance each other out, contributing to a natural equilibrium — or in more cliched terms, the circle of life.

Mass extinction events break those patterns, when the natural extinction rate spikes (more than doubling) over a short amount of geologic time.

Fact Check: The Ice Age Extinction

Although the well-known late Pleistocene Extinction marked the end of many large species (including mammoths, saber-toothed cats, and dire wolves), it does not rise to the level of a mass extinction.

Throughout the history of our planet, there have been at least five mass extinction events — caused by everything from massive volcanic eruptions rapidly releasing greenhouse gasses, an asteroid impact, and rapid fluctuations of sea levels.

Because extinction (over millions of years or through a mass extinction event) is so commonplace, many scientists are interested in studying the few species that have continued to endure — searching for their secrets to long-term survival. New research, conducted by Keegan Melstrom of the University of Central Oklahoma, Randy Irmis of the Natural History Museum of Utah and Department of Geology & Geophysics at the University of Utah, Kathleen Ritterbush also of the Department of Geology & Geophysics, and Kenneth Angielczyk of the Field Museum of Natural History, may have uncovered some of those secrets.

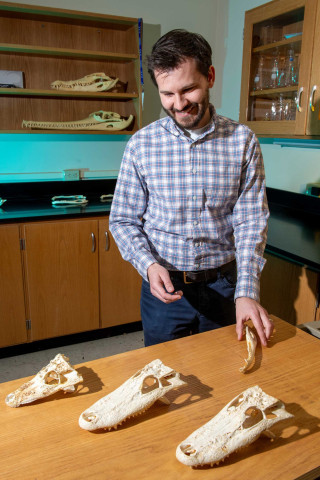

Keegan Melstrom, assistant professor, University of Central Oklahoma with three crocodylomorphs. University of Central Oklahoma

“Extinction and survivorship are two sides of the same coin,” said Melstrom. “Through all mass extinctions, some groups manage to persist and diversify. What can we learn by studying the deeper evolutionary patterns imparted by these events?”

The researchers are studying crocodylomorphs, a group that includes living crocodylians (like alligators, crocodiles, and caimans) along with their extinct ancestors. While many of us think of these ferocious hunters as swamp-dwelling, dinosaur-like creatures, their evolutionary journey provides a different perspective.

Crocodylomorphs have survived the last two mass extinction events, including the asteroid impact that marked the extinction of all non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous Period. This 230-million-year legacy is astonishing, and between a vast fossil record and their modern, roaming relatives, paleontologists have a plethora of resources to help them in their research.

Despite the wealth of information waiting to be discovered through studying this lineage, this paper, published April 16, 2025, in the journal Palaeontology, is the first to reconstruct crocodylomorph dietary evolution — their hypothesis being that at least some of the keys to their continual survival lie in croc eating habits.

How do paleontologists identify the diets of extinct species?

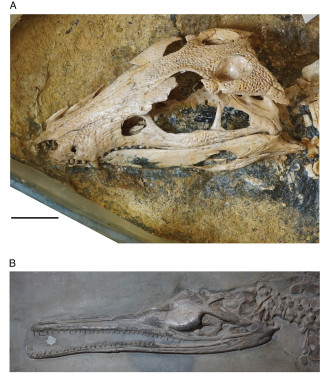

Fossil crocodylomorph specimens exhibiting diverse skull and teeth shapes. A) Araripesuchus gomesii, a Late Cretaceous, terrestrial predator and B) Cricosaurus suevicus, a Late Jurassic aquatic predator. Melstrom et. al. (2025) Palaeontology

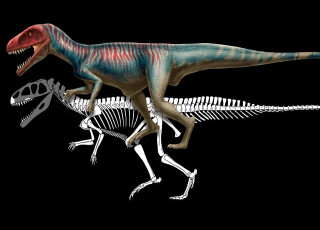

When reconstructing the dietary habits of extinct species, there are a handful of places paleontologists can look for clues. The first indicator is in the teeth. Sharp, razor-like teeth are designed to puncture skin and rip flesh, two things that a carnivore needs to survive. Wider teeth with multiple small points are great for chopping up vegetation. A mix of the two may indicate that the animal ate both meat and plant matter.

Another clue lies in the shape of the animal’s skull, particularly around its jaw. Over time, the shape of an animal’s skull evolves to reflect what it’s eating and how it acquires its food. Short, wide snouts are great for browsing plants, and long, narrow snouts are excellent for snapping at fish underwater. These observations help experts reconstruct the diets of long-extinct species.

But it isn’t just the fossil record that’s worth looking at. Living relatives can also provide valuable insights and comparisons. For their research, the authors of this paper visited institutions across seven countries, examining 99 extinct crocodylomorphs and 20 living crocodylian species — a data set that spanned 230 million years of evolutionary history. This data was then compared to a database of non-crocodylians (including both mammals and lizard species) representing a wide range of diets, habitats, and skull shapes. This allowed the researchers to infer based on skull shape what types of food the extinct species were eating. The team’s conclusions led to some exciting discoveries about crocodylian survival.

Tips for Surviving Mass Extinction

1. Don’t Be a Picky Eater

Today, nearly all crocodylians live in semiaquatic environments and feed on whatever’s nearby, from tadpoles and insects to fellow crocodylians. This kind of eat-anything mentality classifies the group as generalists. They aren’t picky eaters.

The teeth of this fossil Borealosuchus skull typify the toothy grin of semi-aquatic generalist predators that survived the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Jack Rodgers / NHMU

But the fossil record tells a different story: a plethora of crocodylomorphs and their pseudosuchian relatives roamed the earth, living in different ecosystems and surviving on specific diets. The earliest crocodylomorphs were medium-sized carnivores that ate small animals and lived on the land. Despite the mass extinction at the end of the Triassic Period, these land-dwelling generalists were able to survive and thrive.

2. Expand Your Hunting Ground

It was the end of the Cretaceous Period that challenged these survivors the most. During that mass extinction event 66 million years ago (the one that killed non-avian dinosaurs), many of these land dwellers, generalists or not, began to disappear. But the semi-aquatic generalists, which were equally happy on land or in water, like the alligators and crocs we know today, lived on.

There are a handful of theories as to why this might be, but one plausible explanation is that a semi-aquatic lifestyle gives predators an advantage. If they can hunt in a variety of habitats, they have increased access to food. Add in being a generalist eater, and the combination virtually ensures you’ll never go hungry.

3. Look to the Crocodylians

Though none of us can become crocodylians ourselves, it’s clear that we still have much to learn from this ancient, enduring lineage. Continual study of their dietary ecology could provide valuable insights that aid in conservation efforts, allowing us to protect the species and environments currently at risk of extinction.

“When we see living crocodiles and alligators, rather than thinking of ferocious beasts or expensive handbags, I hope people appreciate their amazing 200+ million years of evolution, and how they’ve survived so many tumultuous events in Earth’s history,” said Randy Irmis, NHMU’s Curator of Paleontology and co-author of this paper. “Crocodylians are equipped to survive many future challenges — if we’re willing to help preserve their habitats.”

1 of 6