Top 7 Poisonous Encounters in Nature

Poison dart frog, Dendrobates tinctorius "azureus." Photo: Valerie / Flickr.

By Michael Mozdy

Poison: it's all around us, yet deadly poisonings are rare. Maybe we have learned how to avoid it, or maybe we're all being slowly poisoned without even knowing it. One thing is certain: there are some species that pack such a deadly punch of poison that humans try to harness their power in many ways. This list is inspired by The Power of Poison exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Utah (from October 15, 2016 to April 17, 2017), and in it we explore some of our favorite and unusual poisonous creatures.

Fierce feathers: hooded pitohui

Hooded Pitohui, Pitohui dichrous. Photo: Katerina Tvardikova / eol.org.

One of the very few poisonous birds, the hooded pitohui (pronounced like you're spitting something out of your mouth: "pit-HOO-ee") lives in Papua New Guinea. Interestingly, scientists believe it gets its toxicity by eating the same type of beetle that contributes to the toxicity of the poison dart frog across the world in Colombia: Choresine beetles. The skin and feathers of the pitohui contain a neurotoxin that can cause numbness and tingling if you touch it. Scientists believe the primary evolutionary function of the poison is that it deters lice and ticks, but perhaps it also has to do with helping their offspring survive. Females rub the poison from their feathers onto their eggs when they sit on them, and snakes have been seen eating the eggs and then vomiting them back up. Papua New Guineans call the bird a "rubbish bird" because it cannot be eaten, although if you're desperate enough, it is edible if you first carefully remove the skin and feathers, coat it in charcoal, and then roast it before saying a quick prayer and tucking in. In fact, here's a video from the Travel Channel showing a tribesman eating one.

Death from above: manchineel tree

Warning sign posted on manchineel tree. Photo: ellentk / Flickr.

The manchineel tree, Hippomane mancinella, is one of the world's most dangerous trees. It is found in coastal areas around the American tropics: Florida, the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America. It has shiny green, rhododendron-like leaves and a bright green fruit that looks a bit like a crab apple. Yet nothing about this tree is edible - in fact, it's dangerous just to stand underneath it. When it rains, just a single drop containing the milky sap from the tree can blister your skin. Eating the fruit can be deadly, causing severe stomach pain with bleeding, burns in the mouth, esophagus, and gastrointestinal tract, and possible compromise of the airway. Native peoples in the Caribbean were known to poison the water supply of their enemies with the leaves and Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon died after being struck by an arrow poisoned with Manchineel sap. Even if you wanted to get rid of it by burning it, the caustic smoke can damage your eyes.

Easiest to avoid: poison dart frog

Golden poison frog, Phyllobates terribilis, from NHMU's Power of Poison exhibit. © NHMU, photo by Michael Mozdy.

Perhaps the most famous of the poisonous animals, the small frogs known as poison dart frogs are comprised of over 170 different species and many striking colors. The golden poison frog, Phyllobates terribilis, is the most lethal. In fact, it's the most poisonous vertebrate: the poison in one frog's skin can kill 10,000 mice, between 10-20 adult humans, or two African bull elephants. Their poison is called a batrachotoxin, which prevents nerve cells from firing, thus rendering an animal's muscles in a constant state of contraction, leading to heart failure. There is no known treatment for batrachotoxin poisoning. The toxin comes from their food sources, particularly Choresine beetles. The batrachotoxins do not readily deteriorate, so the frogs can store it in their skin for years after being deprived of a contributing food source. The color of poison dart frogs make them the poster children for aposematism, which is the adaptation of warning signals (color, smell, sounds, etc.) to deter potential predators. This aposematic frog is considered one of the most intelligent anurans (frogs and toads): those in captivity can recognize human handlers within a few weeks, they are very social with one another, they communicate not just in sound but in movement and touching one another, and they are dedicated parents of their tadpoles.

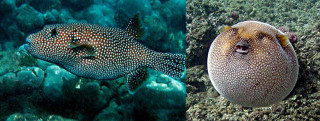

Most likely to be on the menu: puffer fish

Guineafowl puffer, Arothron meleagris, unpuffed and puffed. Photo: Bryan Harry, National Park Service / Wikimedia.

The puffer fish, comprising a family called Tetraodontidae, is a case study in making oneself unappetizing. It isn't a very quick swimmer, so if its fins don't get it out of trouble, it launches plan B, and fills its massively inflatable stomach with water (or air if it's out of water). This creates a near perfect sphere covered in spines. Predators have the unpleasant option of trying to swallow it, which can cause suffocation, and even if they get it down, there's the problem of tetrodotoxin poison. The puffer fish stores this deadly neurotoxin mainly in its liver and ovaries, but small amounts are held in the skin, intestines, and muscle. This leads to the question: why on earth have humans decided to regularly prepare and serve puffer fish as a delicacy? Maybe it's the challenge, but puffer soup, known in Japanese as fugu chiri, is the most common culprit of poisoning. Raw puffer, or sashimi fugu, is less likely to cause death, and is often eaten because it causes intoxication, lightheadedness, and numbness of the lips. Since puffer fish is just behind poison dart frogs on the toxicity scale (100 times more toxic than cyanide), snacking on fugu is no laughing matter.

Worst jewelry: rosary pea

Seeds of the rosary pea, Abrus precatorius. Photo: Scott Zona, Wikimedia.

Abrus precatorius sounds like an incantation from Harry Potter, and eating one of the seeds from this plant can resemble bad magic when a person dies after days of vomiting, convulsions, and liver failure. It is known by many names, such as jequirity, rosary pea, wild licorice, Jumbie bead, and crab's eye. Originally from India, the plant is so invasive that it now grows thickly in tropical and sub-tropical areas around the world, including Florida. The hard-shelled seeds look like ladybugs and contain the deadly toxin abrin (two orders of magnitude more lethal than ricin). They make colorful beads; they are used in percussion instruments and are strung to create rosaries, necklaces, bracelets, and anklets. This is a problem, not just for those doing the stringing, but also because children are drawn to these beads and can suck or chew on them. While the hard coating can sometimes allow the seeds to pass through our bodies without harm, but it only takes one well-chewed seed to kill a human.

Most delicious: death cap mushroom

Growth stages of the death cap mushroom. Photo: Justin Pierce / mushroomobserver.org.

The most poisonous of all known toadstools, the death cap mushroom, Amanita phalloides, has caused some notable deaths in history: Roman Emperor Claudius in 54 A.D. and Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in 1740 (leading to the War of Austrian Succession). The amatoxins in this mushroom are highly lethal liver destroyers - it takes only a half a mushroom to kill a human (which takes days to occur, and often ends in multiple organ failure). Concerningly, the amatoxins are very stable, and cooking, freezing, and drying do nothing to remove them. Death caps are all the more deadly because they can be mistaken for common edible mushrooms like the common field mushroom, the straw mushroom, and caesar's mushroom. If there is an upside to eating them, Bryn Dentinger, NHMU's Curator of Mycology, says, "It is a notorious killer, but is reportedly delicious from some who have survived eating it.”

The tiny toxic terror: cyanobacteria

The green scum shown in this image is the worst algae bloom Lake Erie has experienced in decades. Vibrant green filaments extend out from the northern shore. Image captured by the Landsat-5 satellite in 2011. Photo: NASA Earth Observatory / Wikimedia.

The title of most toxic may go to the tiniest, most simple organism around: cyanobacteria. This name describes an entire phylum of bacteria, also known by the misnomer "blue-green algae" (algae are eukaryotes while bacteria are prokaryotes). These guys are responsible for one of the greatest mass extinction events in history: the Great Oxygenation Event 2.3 billion years ago. Before that time, Earth's atmosphere was oxygen-poor, but this bacteria's unique ability to perform photosynthesis on the folds of the cell's outer membrane (thought to be the precursor to chloroplasts in plants), created so much oxygen that nearly all anaerobic organisms died off. Today, cyanobacteria continue to wreak havoc on a great scale when "algal blooms" in oceans and lakes pollute the water. Cyanobacteria can produce neurotoxins, cytotoxins, endotoxins, and hepatotoxins, collectively called cyanotoxins. The toxic soup they give off when they reproduce unchecked in a bloom can kill thousands of birds, mammals, and fish. What's more, humans can get very sick and even die if they drink contaminated water. As recently as the summer of 2016, Utah Lake had a serious bloom of cyanobacteria. Despite their toxic potential, cyanobacteria are marvels at fixing atmospheric nitrogen into soil (for fertility), fixing carbon into oceans, and creating oxygen for us to breathe. They're probably the most successful organisms on earth, living in nearly every habitat, including hot springs and hypersaline bays. These tiny creatures perhaps best demonstrate the wild series of biological interactions, positive and negative, that constitute life on Earth.

The Power of Poison was a special exhibition that came to us from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. It ran from October 15, 2016 through April 16, 2017.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.