Museum Digitization Project Preserves Archaeological Records

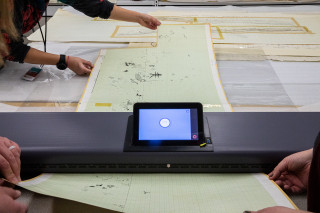

Collections staff feed a historic archaeological map through a large format scanner purchased with grant funding from the Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board. ©NHMU

By Grant Olsen

All of the archeological artifacts received by the Natural History Museum of Utah over the decades have been accompanied by maps, photo logs, and other documents that were created during the surveying and excavation process. These records, called associated records, provide insights to researchers as they study these artifacts to better understand the human past in Utah and beyond.

“We have all these amazing artifacts at the museum,” says Katie Saunders, NHMU’s anthropology records manager. “But the records tell the story. So it’s important to be able to send to researchers what they need to continue learning more about the collection.”

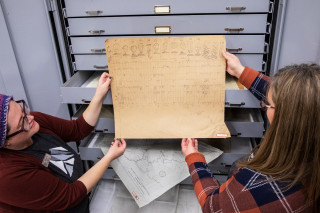

One challenge the Museum has faced is that these one-of-a-kind records were often difficult for researchers to access. And as the decades passed, many were falling into an increasingly fragile condition. Things reached a new level of urgency in 2016, when a treasure trove of previously unknown maps was discovered in the University of Utah Archaeology Center.

So, as part of NHMU’s broader digitization initiative, the Museum launched a concerted effort to not only safeguard these valuable pieces of state history, but also make them findable to researchers worldwide through its digital asset management system.

But how does one digitize a collection of documents that ranges from hand-drawn sketches on tattered graphing paper to a map of pre-dam Glen Canyon that’s taller than an NBA player?

An oversized job like that calls for an oversized scanner. A Contex 44-inch large format scanner, to be exact.

The digitization team quickly realized that to afford such a specialized scanner, they’d need to bring in a partner. Thankfully, the project was made possible through a grant from the Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board (USHRAB) and National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC). Their generosity allowed NHMU to not only purchase the scanner but also hire a part-time student employee to assist with digitizing roughly 1,200 documents in the collections.

Alyson Wilkins, NHMU’s collections digitization coordinator, has spent the past several months focused on this specific project, managing the part-time student employee and even enlisting an entire University of Utah museum studies class to assist in the process.

Wilkins and the team consider these documents, which date back as far as the 1940s, as rare “windows into the past.” For example, many of the maps feature physical sites that have since been destroyed by modern human activity like land development or dam construction. Yet researchers can still connect with the history through the authors of these documents, people who previously visited and recorded these sites.

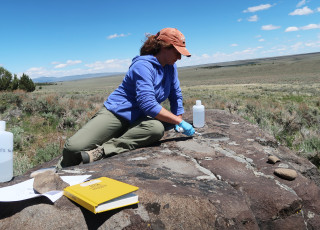

Since the documents were created and used in the field, whether at an archaeological dig or geographic survey, they’re often smudged with dirt and held together with tape. They feature pencil sketches, aerial photographs, profile maps with hand-drawn stratigraphy, and all manner of details regarding the location of archeological sites and their condition at the time.

“They’re both works of art and scientifically significant,” explains Wilkins.

The large format scanner obtained by the Museum can handle anything up to 44 inches wide, making it compatible with all the documents in the collections. As for length, that’s essentially unlimited, which is why the team was able to digitize the 10-foot-long map from Glen Canyon.

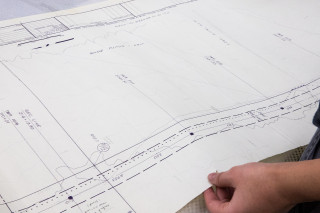

In fact, this jumbo-sized Glen Canyon map has taken on a whole new level of significance as the declining waters of Lake Powell expose archaeological sites that have been submerged since the 1970s. Anticipating the construction of the dam many decades ago, the University of Utah sent an archaeologist down to the canyon to identify places of cultural and scientific significance. Now, researchers can use the digitized map to locate long-flooded archaeological sites and assess their current status.

Scanning and managing these hundreds of documents requires careful collaboration from all members of the team. Creating digital files is one crucial step but must be accompanied by the creation of metadata (such as who created the document, where it was created, and the site number) to ensure the documents will remain as organized and discoverable as possible.

“We’re carefully reading through the maps and transcribing all this information,” says Saunders. “That way you can filter through the metadata and find exactly what you need.”

When all the records and metadata have been successfully connected to the artifacts held at the Natural History Museum of Utah, researchers will have access to a more holistic view of the region’s archaeological sites. And these unique “windows into the past” will be forever protected and utilized by researchers around the world.

Thanks to this digitization effort and the large format scanner provided with support from generous partners, anytime researchers need access to objects and their associated records, the documents are just a few clicks away.

Grant Olsen is the author of Magnus Somnia, Rhino Trouble, Jasper and the Yeti, and is a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.