Bringing Dinosaurs to Life Requires a Paleontological Dream Team

By Grant Olsen & Mark Johnston

With 2023's DinoFest theme, "Bones to Beasts," the Natural History Museum of Utah will explore how paleontologists go from locating dinosaur fossils in the ground, extracting them from the rock, preparing the bones in the lab, and ultimately putting them on display. It’s a lengthy process that requires the expertise of many different individuals.

“Our expert DinoFest speakers will discuss everything from fossil excavation to how paleoartists use a combination of scientific data and informed speculation to bring dinosaurs to life," says Randy Irmis, NHMU’s chief curator and curator of paleontology.

Let’s look closer at these various stages of paleontological work that brings dinosaurs back to life at the Museum.

Fossils in the Field

Fieldwork conducted by NHMU is carried out by teams of staff paleontologists and a dedicated corps of students and volunteers, who bring a mix of ages, expertise, and backgrounds to the party. For some of them it’s their very first time looking for fossils or joining an excavation, while others have experienced the thrill of discovery numerous times before.

Such a discovery starts with prospecting for bone fragments weathering out of hillsides or other embankments. Upon sighting a few small fragments, the field team will trace the fossils to the source layer where more bone is exposed. Tests are then carried out to see if it’s worth conducting a broader excavation.

The length of a dig can range from a few days to a few months with some key factors determining the worthiness of the endeavor. These include how rare the discovery is, how much fossil is still present, and how much rock is covering the bones. In the case of the discovery of the armored dinosaur Akainacephalus johnsoni, it took weeks of cumulative work over 3 field seasons just to extract the fossil from the ground.

Before, during, and after any extraction, scientists are also surveying and logging details about the discovery site for research purposes. A site can include multiple species with bones of one intermixed with those of others. This demands scientists to work diligently to identify and label fossils as they come out of the ground. Great care is also taken to wrap the remains in protective plaster casts before they’re transported by hand or helicopter to a waiting truck for transport to NHMU.

Working in the Lab

After a specimen is transported to the Museum via truck and trailer, another dedicated group of volunteers takes on the tedious process of removing any remaining rock from the fossils.

“If it was just me it would take me forever to finish a specimen,” says Tylor Birthisel, preparator and paleontology preparation lab manager. “The lab at NHMU is powered by volunteers. They are the reason we have so many cool fossils prepared that we can do science on and display.”

Volunteers working in the prep lab are sometimes the same who helped recover the fossils in the field. And while they come from varied backgrounds, they all share a key trait: Patience.

Patience is mandatory because when fossils arrive from the field they are still encased in a surrounding rock matrix, sometimes up to hundreds of pounds of it. Differentiating between rock and the priceless fossils inside requires a keen eye and delicate work with microscopes and air scribes, chipping away like a dentist with a drill.

The time it takes to clean and prepare bones depends on the hardness of the rock, how delicate the fossil is, and how large or numerous the pieces of fossil are. Smaller specimens in soft rock might only take a few hours, while a similar sized specimen in harder rock could take weeks. For Akainacephalus johnsoni, the combined prep work reached into the thousands of hours, 800 of which were spent on the skull alone.

“All I could see was the back of the skull, just a couple of bones sticking out,” says Randy Johnson, a dedicated volunteer who played a large role in preparing the skull. “It was really exciting to see something developing and I wanted to find more of it to see what it looked like.”

Efforts of volunteers like Johnson are vital not only to the operation of the prep lab, but also to the study, identification, research, and eventual display of the dinosaurs they work on.

Once fossils are completely extracted from rock—and at times carefully glued back together—more work is conducted to catalog each bone and build secure archival housings for study and storage, this time by a team lead by paleontology collections manager Carrie Levitt-Bussian. And while most original fossils will spend their lives stored away in collections rooms for research, in some cases a specimen is deemed worthy enough to display to the public.

Selecting Dinosaurs for Display

Museums don't have enough space to put every discovery in their collections on display, but when certain criteria are met, a mount of a skeleton is put on exhibit. Considerations must first be made as to whether the fossil is complete enough to make a reconstructed skeleton, if there’s enough space in the exhibit to accommodate an addition, and whether it fits the theme of an existing exhibit.

If those criteria are met, scientists like the Museum’s chief curator and curator of paleontology, Randy Irmis, begin work with fossil replica experts, like Gaston Design, to make replicas of bones for display. This process is rarely straightforward, especially when dealing with an incomplete skeleton of a new species like Akainacephalus when other examples cannot be drawn from. Thankfully, scientists have one advantage in that all skeletons follow a similar body plan.

“If we are missing the right femur, we can use the left femur for reference,” says Irmis, noting that scientists can often fill gaps in a skeleton based on lots of lines of evidence, such as related species.

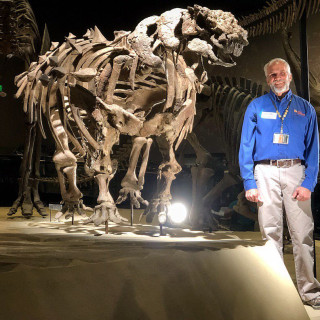

When the skeleton is completed, a mount is produced and delivered into the hands of the Museum’s exhibits team, led by exhibits director Tim Lee.

“It’s science and art coming together,” says Lee, whose team helped install the completed mount of Akainacephalus, the last phase in the dinosaur’s years-long journey from discovery to museum (Some would say the journey is 76 million years long since it started with the life of the dinosaur!)

Whenever space is available, Lee works with his team to create an educational experience for Museum visitors and position dinosaurs in dynamic and engaging displays. And, like the science of paleontology that delivers new additions to the museum floor, exhibits are always evolving.

It Takes a Village to Raise a Dinosaur

This process, from “Bones to Beasts,” takes a huge collaboration like few others outside of museums. But efforts are always worthwhile if the resulting mount inspires guests to learn more about dinosaurs like Akainacephalus, first discovered as a pile of dusty fossils in the desert.

“Most people will have face-to-face experience with dinosaurs, whether through a museum or pop culture,” says Lee, “And how it impacts you on a personal level varies wildly. That’s the power of paleontology.”

Want to learn more about the collaborative world of paleontology? Be sure to attend DinoFest "Bones to Beasts" on January 28 and 29 at NHMU. Click here to view the DinoFest speaker lineup, which will include Birthisel, Levitt-Bussian, and Lee.

You can also read more about the discovery and description of Akainacephalus johnsoni here.