Explorer Corps Marker: Emery County

Find the Marker

The Emery County marker is located outside of the Museum of the San Rafael at 70 N 100 E in Castle Dale. It highlights the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, which is about 30 miles northeast of the Museum.

GPS 39°12’46.5624”N 111°1’2.9352”W

Dig Deeper

About an hour outside of Price, Utah, among the gray and maroon hills of the Morrison Formation, there lies a great dinosaur boneyard. Known as Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, this place is the centerpiece of Jurassic National Monument and has attracted paleontologists for over a century. All told, more than 12,000 bones of Late Jurassic animals have been found at this quarry – the vast majority of them belonging to a large carnivore named Allosaurus. Therein lies the site’s mystery.

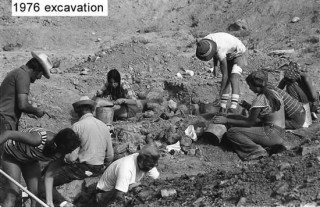

The site that would become to be known as Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, or CLDQ, attracted curiosity long before paleontologists started to excavate the site. Indigenous people in the area almost certainly noticed the vast accumulation of bones here, and by the late 1800s ranchers began talking about the fossil-rich spot in the desert. Scientific studies began in 1927, when geologists from the University of Utah made an expedition to the site. From there, institutions such as Princeton University, Brigham Young University, the Natural History Museum of Utah, and the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh have all pondered over the site and how it came to be.

Much like the Carnegie Quarry of Dinosaur National Monument to the northeast, CLDQ is Late Jurassic in age and contains many of the same dinosaurs. Jurassic classics such as Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus, Camptosaurus, Ceratosaurus, and more have been found here. But of the thousands of bones excavated from the site – the majority of which are in the collections of the Natural History Museum of Utah – about 75% are assigned to Allosaurus fragilis. That’s strange. Herbivores are often more common in these sorts of deposits than carnivores, with CLDQ standing out as an exception.

Experts have proposed a slew of ideas to explain why Allosaurus is so common at the site and how CLDQ came to be. Hypotheses include a sticky predator trap where mired dinosaurs attracted hungry Allosaurus, dinosaurs killed by intense drought, a pond turned toxic by bacteria, dinosaur carcasses washing downstream from elsewhere, and others. While there are many bonebeds in the Morrison Formation, CLDQ remains a head-scratcher for experts given how unusual it seems compared to others that formed around the same time.

The most recent analysis of CLDQ proposes that the site represents multiple periods of deposition and drying. Bodies and bones accumulated on the nearby landscape during the dry season, only to be washed into a river channel when the rains returned. The torrent was so intense that the river jumped its bank and spilled over into a pond – a stagnant body of water where dinosaur remains settled and were buried, a cycle that played out several times.

Even so, no one really knows why Allosaurus is so abundant at this site but not others. Perhaps there was a mating or nesting ground nearby, or some other draw to the area that made this place important for the animals. Nevertheless, the huge collection of Allosaurus bones – young and old – draws researchers to NHMU each year to study everything from how these dinosaurs grew to how they moved. The extremely large sample size of Allosaurus material allows paleontologists to test hypotheses that are not possible for most dinosaur species, allowing us to understand more about how Allosaurus lived even if we still wonder about why they died.

Want to Go Farther?

Drive to the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry Visitor Center to see the historic quarry itself.